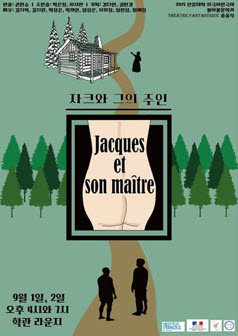

At the beginning of every fall semester of Seoul National University, six foreign language departments of the College of Humanities collaborate to hold the annual SNU Foreign Languages Drama Festival, in which each department performs a theatre production in their affiliated language. For this year’s 19th Drama Festival, Théâtre Fantastique, a fantastic name for the French Language and Literature Department’s theatre club, presented Milan Kundera’s “Jacques and His Master” (Jacques et son maître) on September 1 – 2 at the Student Center. Perhaps reflecting the spotlight sentiment of the modern era, and Milan Kundera’s quote, “I’ve had an overdose of myself!” the production by Théâtre Fantastique enrapt the audience in its philosophy of self-mockery.

The Franco-Czech writer Milan Kundera wrote the play in 1971, during a time when publishing liberal thoughts were banned by the Soviet authority. Nevertheless, his dissident status instills the spirit of the enlightenment and intellectual freedom into his skeptical play that questions authorship, life, and existence. This existential black “comedy” was a homage to Denis Diderot’s novel “Jacques the Fatalist” (Jacques le Fataliste) in a time of political and artistic oppression.

A moment of Jacques’ monologue

In accordance with the subversive air, Théâtre Fantastique’s production playfully reinstalls the art of self-mockery from paper to live theatre. KWON Hyun Seung (College of Liberal Studies), director of “Jacques and His Master,” explains that in the original script, the characters deride and ridicule the playwright in many of the scenes, but in the theatre version, he decided to change the subject of condemnation from the writer to the director. Kwon managed to whole-heartedly entertain the audience by allowing himself to be directly criticized by the actors who nonchalantly blurt out, “Why should I be the one to be hanged? It’s because of the words written above. Oh, my master! The director who made us play our parts must be one lousy director, the most terrible and ignorant, the king of all the directors!”

While faithful to the conventional production of the play, another significant change comes from directing the actor of Bigre to also take on the role of Marquis des Arcis. This double role, describes Kwon, was to demonstrate the recurring themes and similarities between the overlapping stories. The emphasis on repetition and mimicry of stories weaves the audience into the play’s following of Jacques and his master on their ambiguous and timeless journey of love and revenge, friendship and betrayal.

Different characters’ stories incessantly interrupt Jacques’ story of his true love, therein creating an endless narrative loop of a story within a story, a play within a play, and lives that are repeated. Jacques nostalgically recalls how he spent a night with his best friend’s beloved. Contrastingly, the master laments how he was betrayed by his best friend who stole his beloved. Kwon voiced that, “Everybody worked to master his or her part. But at some point, people were eagerly stepping into the roles of the other characters and staff members, sharing concerns and influencing one another.” This explains how the complicated relationships and various narrative levels could be successfully delivered to the audience.

The multi-level textual interference is mirrored in the stage setting that had two rooms on different levels. Act One ran on a simple stage setting consisting of a wooden platform, and a ladder that climbs up to a small room. Overall the set changes three times, once to capture the scene of the inn owner’s act of revenge upon her lover, another to highlight the bare country roads, and the last to demonstrate the unjust incarceration of Jacques. The undecorated and monotonous setting illustrated the fruitlessness of existence. Only on specific occasions did the producers use color to emphasize a particular point. The nakedness of the atmosphere visually highlighted the warm glow arising from the intensity of the actors’ bodily movements and energized expressions.

With limited funds and only eight actors (produced by a total of 26 personnel), Théâtre Fantastique managed to place the spotlight on each one of its actors. Indeed, not one character could be named a minor role as all were interconnected in the others’ story. “The specific individuality of each role was also incredible,” Kwon remarked. “This play could be produced the way it was because of each individual involved. If one person was replaced with a different person, the result would have been a different play.”

Nevertheless, the specific individuality of each character did not diminish the director’s intentions. Kwon elucidated the disillusioned and cynical ending of the play by stating that he hoped the play would seem like one big joke: “Rather than emphasizing the heavy burden of the immoral and sexual content, I wanted to juxtapose these features in the aspects of playfully mocking life.”

The curtain call

Nullifying life (of the characters), and the creator of life (director) who created the meaningless cycle of life (the play), the play concludes in a manner that the work itself is a serious statement of its existence, and at the same time, a funny pleasantry. KANG Sung Hyun (College of Liberal Studies) delineated his viewing experience as one of delightful humor, but serious at the same time. He said, “Jacques and his master both fail in their search for happiness, even though they played two opposite roles of the assailant and the victim of a similar story. This kind of melancholy and cynicism of life struck a chord in my mind. Nonetheless, the play had its comical moments, entertaining thoughts on life with a feathery airiness.”

While Kundera’s original homage mocked the art of writing, Théâtre Fantastique reinterprets and throws playful jabs at the unbearable heaviness of theatre itself. Perhaps passion is the only thing that persists and endlessly exists in this anguish of the meaninglessness of life. For the most memorable part of “Jacques and His Master,” was the aureoled glow steaming from the passion of the actor and actresses in rebellion to the notion of the theatre’s nothingness.

Written by Su Hyen Bae, SNU English Editor, suhyenbae@snu.ac.kr

Reviewed by Eli Park Sorensen, SNU Professor of Liberal Studies, eps7257@snu.ac.kr